I was surprised when I received a commission to build an English theorbo.

The commission was unusual because few modern lute makers have built them and I doubt that many others have seen or heard one. My client is a member of an ensemble that had a program of late 17th

century English music organized for touring and dates in the United

States were on their calendar.

On the left is my finished English theorbo. It looks a lot like a small Italian theorbo except for the extension where four small nuts are arranged at unequal intervals along the extension with a plate of boxwood glued to the front of the theorbo head serving as the fifth diapason nut. I will explain the reasons and benefits of this arrangement further along in this post.

Italian theorbos had made their appearance in England early in the century and had

become popular for voice accompaniment and consort. As well, twelve course lutes with the diapasons arranged along a straight second pegbox were to become popular a little later for the same reasons. Jumping ahead to the early

1670s a particularly English variation appeared, double strung and

tuned in G with the first course and if the lute were large enough, the second tuned down an octave. The diapasons were arranged as described above.

There were at least two variations of the English theorbo that are documented either in the iconography or surviving documents. Below is an image of Thomas Mace's Dyphone, built by him, and described in his

book Mace's Monument. As you can see the Dyphone is two lutes in one. The left hand part is a twelve course lute. While the right hand side is the theorbo. Note: the facsimile of Mace's Monument seems to have come under copyright. However a plain text version can be read Here

The facsimile

I enlarged and cropped the theorbo half of the Dyphone which now shows in better detail the curious construction of the extension.

The diapasons are mounted on three semi-circular wooden "bridges" which function like bowed instrument bridges with a foot planted on each side of the extension. The longest diapasons ride on a plate glued to the front of an odd theorbo head. Mace describes the spacing of the diapason bridges and the reason therefore, "that each diapason descends gradually step by step; by which means, the whole number, both of short and long strings speak uniformly and evenly to themselves which is a very considerable matter in any instrument". I will return to this description when I describe how I arranged the diapasons for my lute.

Andy Rutherford built three theorbos using Mace's design; for Stephen Stubbs, Lyle Nordstrom and one for himself.

I saw his first one at the Amherst Early Music Festival around 1996. I was building a lot of theorbos then and I was delighted to see an English theorbo. I was astonished by the method of mounting the diapasons and remember thinking - No way.

In a recent phone conversion Andy and I discussed many issues with the English theorbo and I'll relate a few of them: Andy said initially he treated the arched bridges as free standing structures but eventually it was necessary to glue them in place because they kept falling over when tuning the instrument. He is a fan of gut strings and he uses them on all of his personal lutes. When you listen to the video link at the end of this paragraph you'll understand Andy's preference for gut strings and Mace's reason for designing the theorbo half of his Dyphone with stepped diapasons and octave stringing. On string tension his reply was reminiscent of the advice to tune your chanterelle near the breaking point and follow with the other strings. Andy chose a position on the theorbo's extension, picked out a promising string from his collection and tuned it up until he liked the sound. Then he sent the string and other relevant information to his string maker and asked for a complete set.

Here is the link that Andy kindly sent of him playing Mace's composition Fancy- 13th Variation on his English theorbo. You will get a good look at the entire instrument.

Play here

Around the same time David van Edwards built an English Theorbo for Lynda Sayce based on the second variation of the English theorbo as represented in the painting Lady with a theorbo by John Michael Wright (Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus, Ohio). His website includes photos and a description of his English Theorbo. David van Edwards English theorbo In addition, David also includes his article, Talbot's English Theorbo Revisited that was published earlier.

|

| Lady with a theorbo |

Now for my take on the English theorbo. Since I had sworn off Mace's design nearly 30 years earlier I certainly was not going to change my mind. There was some urgency in having the instrument ready for my client's rehearsals so I moved along quickly. I started by thinking of the Lady's theorbo as a model for the instrument that I was about to build, not just the treatment of the diapason nuts, but also for the fullness of the face and the depth of the bowl. I noticed that she was holding the lute far enough from her body to suggest that the lute's bowl was deep and rounded rather than flattened. The lute has a single rose which I thought appropriate. I can't recall seeing an English portrait from the seventeenth century that includes a lute with a triple rose.

I was not interested in trying to copy the Lady's theorbo or even building a one of similar size. I was interested in building a lute that might have been built in England or at least assembled there from parts of of older or damaged instruments much like the lutes of Thomas Edlinger in Prague.

Since the ensemble that hired my client played robustly I thought a large theorbo was needed. Thomas Mace agrees. He recommends two lusty full-sized theorbos when paired with two violins. I admire the lutes of Wendelio Venere particularly his large theorbo built in 1606, E. 548 conserved in Musée de la musique, Paris. The details of this instrument's history align with my fictional story. This Venere was not originally a theorbo but probably a seven or eight course octave bass that was converted to a theorbo at an unknown date. You can see the instrument

HERE .

I hardly had time to draw a schematic of the instrument before I received word that the group's travel coordinator had vetoed the idea of traveling with a large theorbo.

I had sold myself on the idea of using a Venere as a model so I decided to look at the smaller Venere theorbo KHM C.47, Vienna.

I unrolled my rumpled but much appreciated plans of C 47 and studied its measurements (367mm wide, 559 to the neck joint and 153 deep). The original neck is only 80 mm wide at the joint with the bowl. I would need to cut the front block back to accommodate a wider joint for the new extension. That would make the block too small so I decided to increase the length of the bowl to make up for the discrepancy.

I added 8mm at the widest point of the bowl while maintaining the elegant profile.

This is a photo of one of my 1611 Veneres from the late 1990s.

I didn't think this shape of back expressed the style that was favored during the 17th century in England and I have already stated that I wanted my lute to have a deeper depth.

In fact Mace is very clear that the old lutes build by Maler, Frei and Unverdorben were the most sought after and demanded the highest prices. Their backs were not flattened, but more or less half round. This is a seven course lute by Marx Unverdorben, Mùseu de la Musica, Barcelona. I adopted this shape for the arch of my bowl but retained the face contour of the 1611 Venere. Search "Unverdorben" in my blog's search box for my story on this lute.

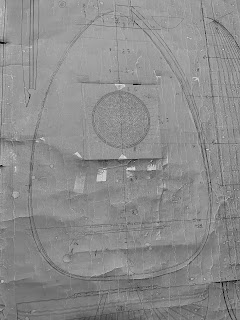

Satisfied that I had enough information to build a mold I drew a full size face of the instrument on a large piece of poster board and the side profile on another poster board as well.

I like working on open molds because it allows me access to the underside of each rib as I assemble the bowl. However, there must be enough cross-sections to insure that the proper rib curvature is maintained.

Now that all of the preliminary work is done I can actually start building the lute.

I decided to use 21 ribs of bird's eye maple, inspired by the Barcelona Unverdorben, separated by 1.5mm walnut spacers. I chose twenty one ribs simply because I like working with that rib width.

The ribs came together neat and secure and the photo shows the shape and depth of the bowl.

Several large steps later the lute was ready for its theorbo extension. I ordered the case long in advance because I wanted to make sure the lute and case were compatible.

The alignment of the extension was critical, not only for aesthetic consideration but also for the distribution of forces exerted by the strings. I like to keep these forces directed into the neck and bowl of the instrument by aligning the bass edge of the extension on a line that is parallel to the center line of the soundboard.

Now the details of construction.

In this much later photo the extension is nearly finished but it is only tack glued to the neck. You can see how each course moved closer to the edge of the extension until the eleventh course, nearest the theorbo head is partially off the edge of the extension.

Achieving the proper alignment required a lot of trial and error which I did with the aid of a dummy plywood extension.

Unlike Thomas Mace who spaced his diapasons by whole numbers I spaced mine by uniform string tensions with the effect of minimizing disparities in feel and volume. The results seem to be about the same.

In the following photo I am checking the alignment for the final time before I glue the extension into its joint. I tied sewing thread to the bridge holes of the 8th through the 11th string holes and stretched the strings over small walnut posts, checking the clearance both within the courses and between them.

The posts sit in 4mm deep recesses that I chiseled out. At this point they are not glued in place.

Once I was satisfied that my alignment was going to work I removed them, contoured their front surface with a curved relief and shaped individual bone nuts that I glued on top.

In the drawing of Mace's Dyphone it is difficult to make out the shape of the theorbo head. I wanted to give him a shout out and make something like a tea pot spout - Thomas' teapot.

The head sits partially off the edge of the extension so I glued a platform to its edge. The head is being aligned and held in place by a rubber band. The excess wood will be removed before I glue the theorbo head permanently.

Here are closeup photos of the different parts of the finished extension.

The strings are a combination of New Nylgut on the first four trebles, followed by a carbon fifth and then KF fundamentals with New Nylgut octaves on the sixth and seventh.

The diapasons begin with a carbon eight with a New Nylgut octave. The ninth is a KF with a Nylgut octave and the rest are KFs with carbon octaves.

I turn the pegs by hand using only calipers.

The peg wood is Castelo boxwood stained black and sprayed with a light coat of lacquer. The pips are small map pins inserted in predrilled holes and glued with Crazy Glue.

The tenth course post and nut are located very close to the edge of the extension while the eleventh overhangs slightly. The teapot carries the twelfth and thirteenth courses with a medallion of European boxwood glued to the front of the theorbo head.

The tops of the nuts are not on the same plane. I was concerned that the courses would slap together so I added one or two millimeters in height progressively to each one. That was not necessary as the end of the extension bows up under string tension, putting each course on a separate plane. The extension is finished with multiple coats of rubbed tung oil.

The bowl is varnished with a true oil and resin varnish that I bought at a paint sale just before the manufacture of oil paints were prohibited. I have managed to preserve it in small containers.

The top is alpine Swiss spruce air dried for six years. Waxed and rubbed with bees wax.

The rose is inset. This fits in with my fictional story that the lute was built or assembled by an English luthier. Samuel Pepys records in his diary on February 17, 1659, "... then came Mr. Hills the instrument maker, and I consulted with him about my lute and my viall." (quote from Pepysdiary.com)

We are unlikely to learn much more about Mr. Hills but it is clear that he was a skilled luthier favored by a privileged clientele.

Over my career I have assembled a collection of roses from severely damaged lutes that came back to me for repair or replacement. This rose came from I one of my Venere theorbos. That seems appropriate. I feel that I am taking part in a living history of the lute by reusing and prolonging the artifacts of the past. An historical performance, so to speak.

More photos

A view inside. The short bar near the top of the soundboard is positioned under the twelfth fret.

The long view. The neck core is quartered sitka spruce veneered with English walnut. The extension is solid English walnut. This walnut comes from eastern Pennsylvania, cut from descendants of trees planted by English colonists.

The neck is edged with ebony to protect the softer walnut from marring by the fret knots.

The walnut veneer has a little figure in the grain. I cut the veneer from solid timber.

I made the butt end of the extension flattish with a sharp edge. This is a feature on the Venere theorbo C47. The construction is much easier to make and easier to fit to the instrument's neck. This and the narrow width of the neck leads me to believe that the lute was originally a bass lute converted to a theorbo.

Lutenists find the chanterelle bracket a useful addition.

Dimensions

The total length: 150 centimeters

Strings lengths:

Fretted. 78.9 cm

Diapasons: 96.7 (8), 102.4 (9), 113.3. (10), 121.2, (11), 129.4 (12 & 13)

Length of the soundboard to neck joint: 55.4 cm

Width of soundboard: 37.3 cm

Depth of bowl: 17.3 cm

String span at bridge: 15.3 cm

String span at nut: 49 mm (seven courses)

Total weight: 1235 grams

I started the theorbo during the second wave of Covid and finished it during the third. My client's tour was cancelled and he walked away from the commission: a different outcome than I expected.

That said, building the lute was a challenging, absorbing and an enjoyable experience for me.

All photos by the author

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

%20copy.jpeg)

%20copy.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

%20copy.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)